Long before Linkedin connections and digital rolodexes, there was the visiting card: a small rectangle of paper, often no larger than a matchbox, that served as a symbol of presence, identity, and etiquette.

For centuries, it was the gentleman's or lady's formal announcement, left delicately on a silver tray in a drawing room or discreetly delivered by a servant to the household.

Today, in a world oversaturated with contact information and digital touchpoints, the visiting card is reemerging as a refined gesture. The modern revival, led by designers, creatives, and cultural purists, taps into a desire for tactility, personal connection, and slower modes of social exchange.

A history of subtlety

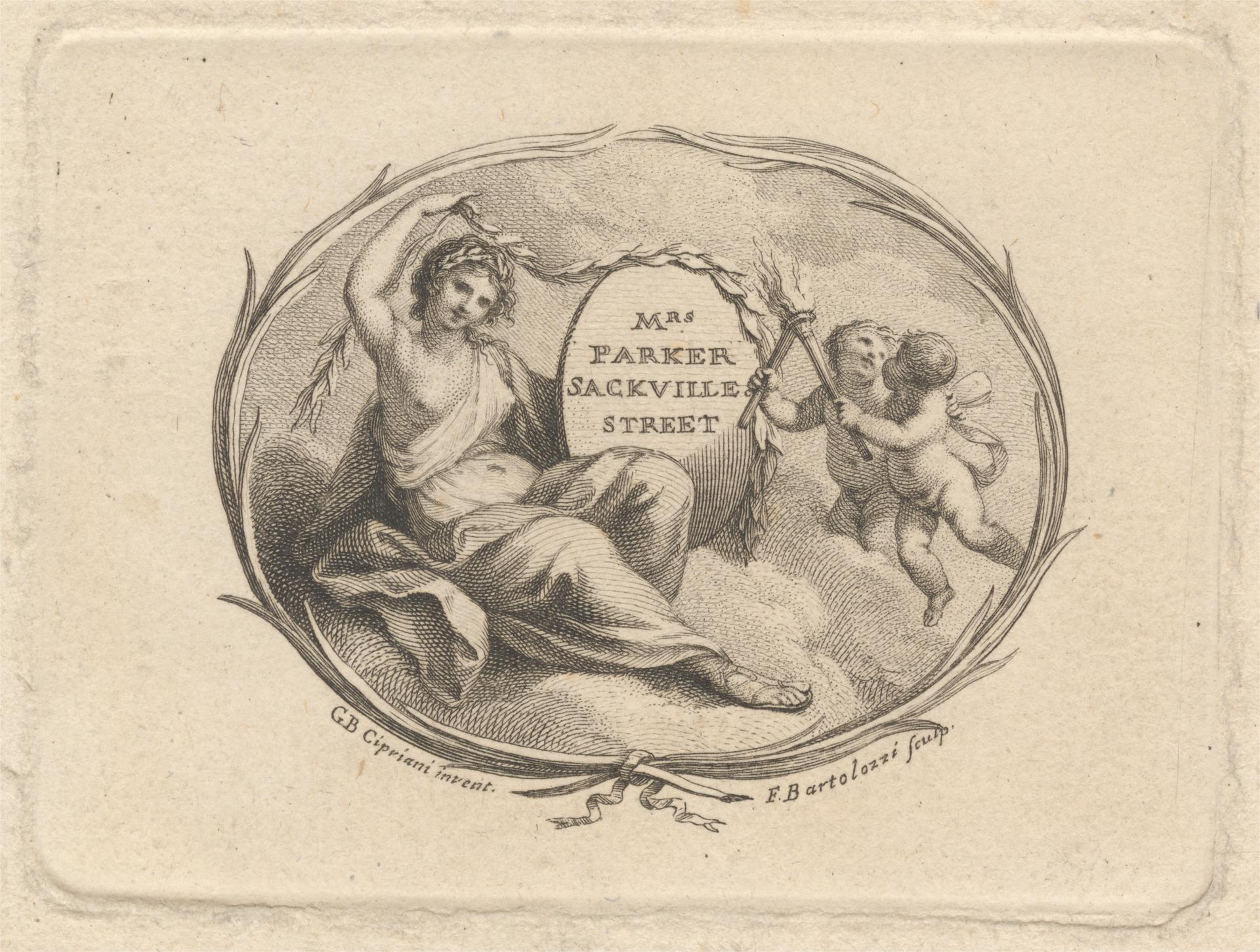

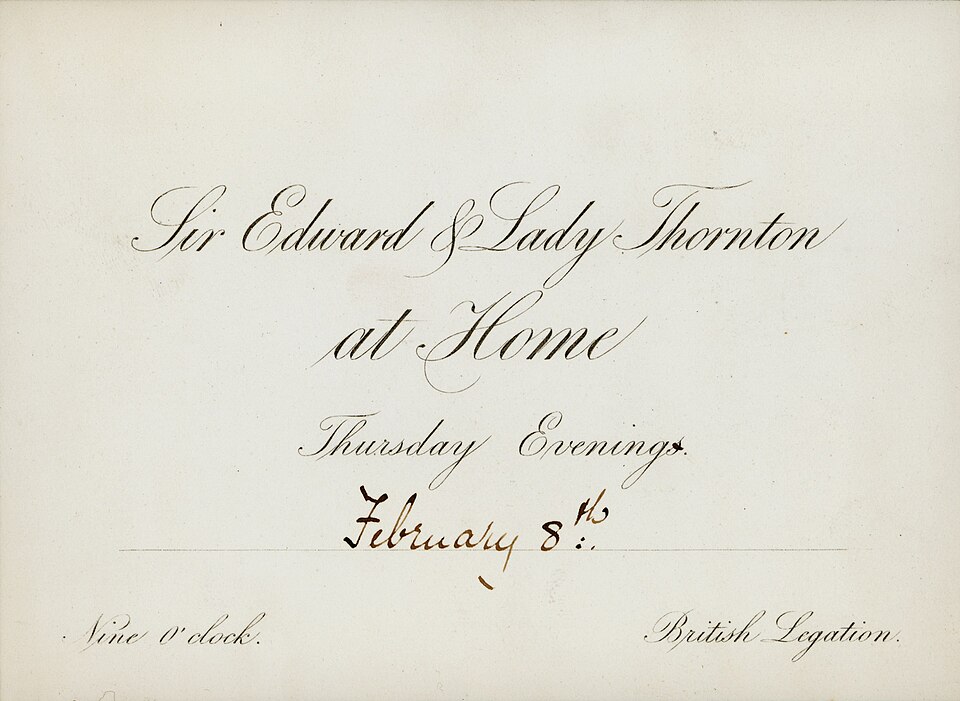

Visiting cards first gained popularity in 18th-century Europe, particularly in France and England, where they were essential to polite society. The rules were exacting. A card's size, typography, and even its corner folds could communicate specific intentions.

A turned-down corner might suggest the call had come in person. A lady might have her husband's name included; a bachelor might leave a card printed in simple block letters, with no address, just his name.

These cards were for civility. Unlike business cards, which traffic in job titles and logos, visiting cards functioned more like social passports. Sort of like an elegant handshake on paper.

The return of something personal

While the age of calling cards has largely passed, their spirit has found its way into modern design culture. For those attuned to a more deliberate pace of living, the visiting card offers a counterpoint to digital noise.

Today's versions, sometimes called social cards, are used not only for personal introductions but for specific situations.

A painter might hand out a card bearing only a name, a studio address, and a hand-inked symbol. A woman might carry her own monogrammed card for encounters that don't warrant a phone number but deserve acknowledgment. Parents increasingly craft minimalist "playdate cards" bearing their child's name and contact information, a gentle nod to yesteryear's etiquette in the schoolyard.

Design that speaks softly

Modern interpretations of the visiting card are distinguished by their sleek look. Rather than glossy graphics or aggressive branding, they favor weighty paper stock, embossed initials, blind debossing, or subtly foiled edges.

The creative types opt for circular or oval shapes, challenging the rigid geometry of their corporate cousins. Others are printed on bamboo paper, or recycled cotton stock, conveying the cardholder's values through material alone.

Even technology has found its place in this renaissance. QR codes and NFC chips discreetly embedded into cards now allow recipients to access a digital profile or portfolio, but the card itself still leads the interactions.

Culture, satire, and the card as status symbol

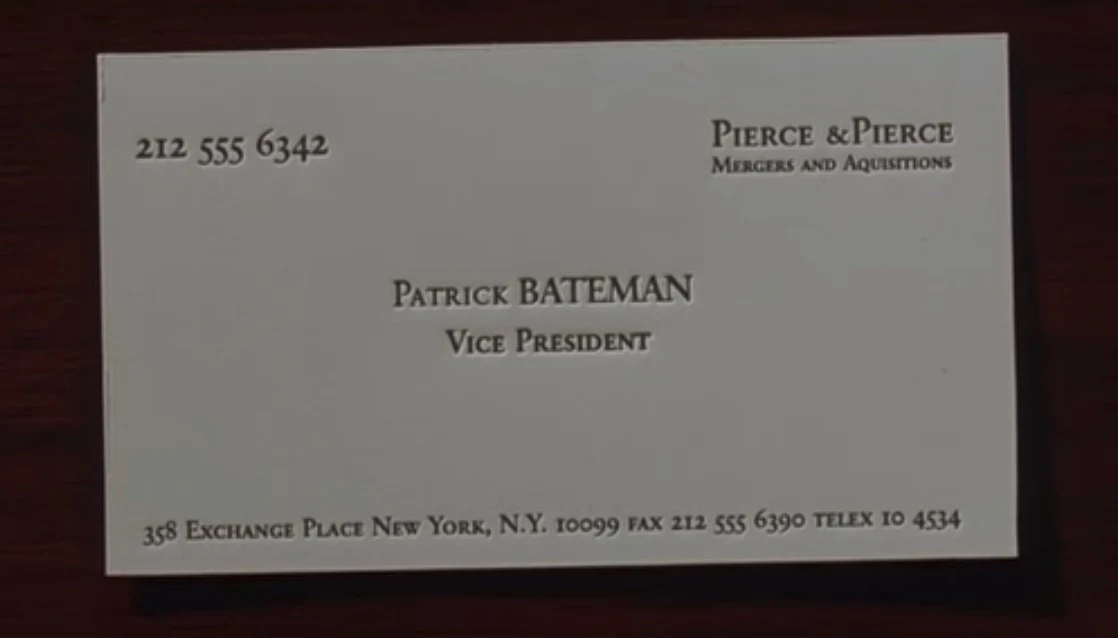

Nowhere is the cultural weight of the card more theatrically explored than in American Psycho (2000), where a group of Wall Street colleagues obsessively compare the minute differences between their business cards: off-white versus bone, raised type versus watermark.

The scene has become iconic because of what these cards represent: status, exclusivity, taste, and the razor-thin distinctions that define competitive social circles.

The films skewers the vanity of 1980s success culture, but the business card scene lands because it reveals something truer than satire: in certain rooms, the card is a person's entire résumé, reputation, and rank distilled into 3.5 by 2 inches.

Why they still matter

In a society increasingly ruled by algorithm and automation, the act of offering someone a card is quietly radical. It's an offering of self, rather than a service. In that, the visiting card still performs its original role and that is to introduce and linger.

To carry a visiting card today is to suggest that not all connections need to be transactional. It is an affirmation of personal style, of tactile communication, of presence.