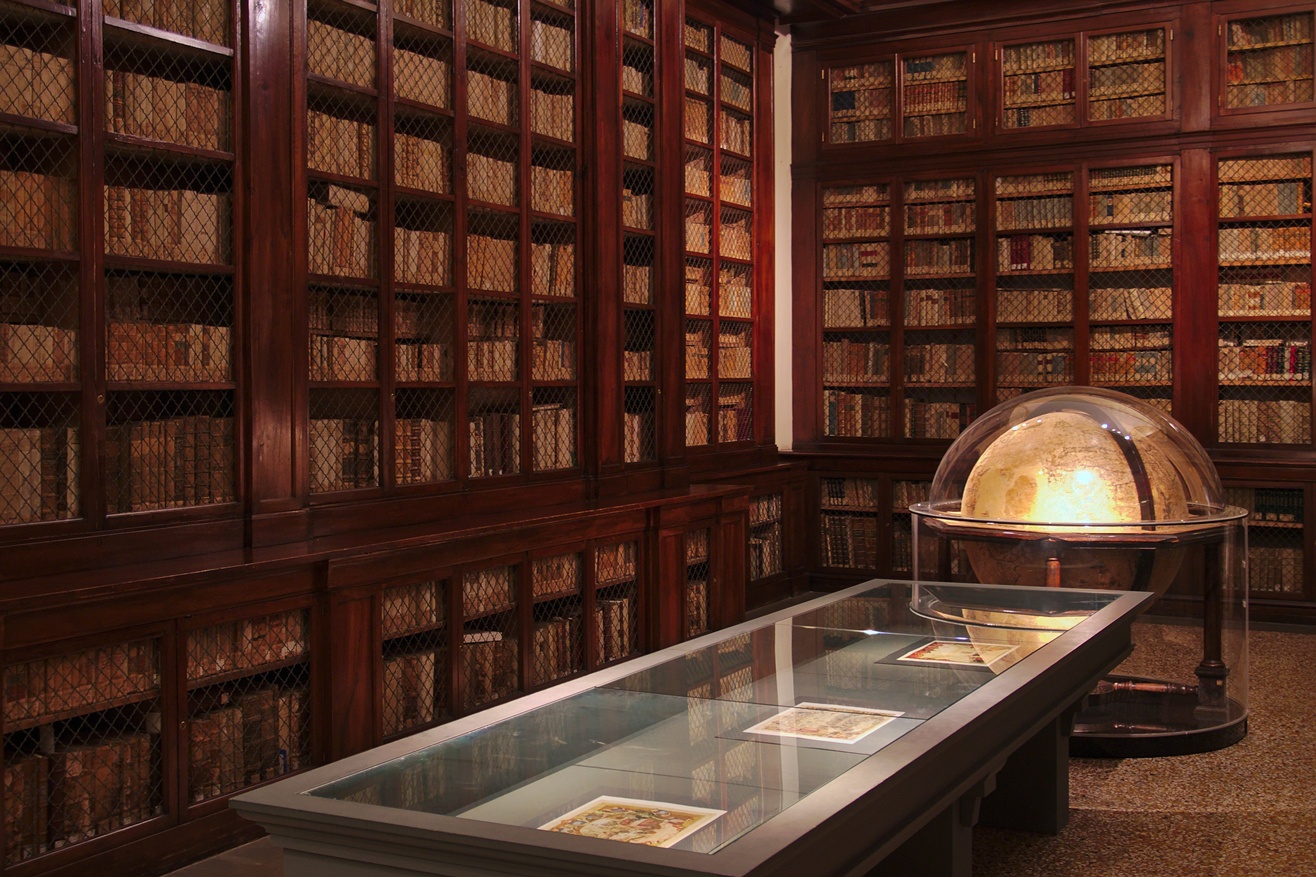

Founded in the late 11th century, the University of Bologna holds the distinction of being the oldest continuously operating university in the Western world.

For most of its history, its lecture halls were the exclusive domain of men. Yet, across a span of nearly five centuries, two women broke through that tradition—first in law, then in science—earning places at the lectern of one of Europe’s most prestigious academic institutions.

Bettisia Gozzadini: The medieval jurist

In the early 13th century, Bettisia Gozzadini was born into a prominent Bolognese family. She pursued studies in law and philosophy under some of the city’s most respected jurists, graduating with a law degree around 1237, a rare achievement for any woman of her time.

She began by teaching at her home until 1239, when, at the insistence of the disciples who wanted to attend her lessons, the Bishop Enrico Dalla Fratta allowed her to teach at the university.

Contemporary accounts describe her as an accomplished orator, even delivering the funeral address for the bishop in 1242. Later retellings added flourishes to her story, claims that she disguised herself as a man to attend lectures, or that she veiled her face while teaching to avoid distracting her students.

While some of these details may be embellishments from later centuries, Gozzadini is recorded as the first woman to teach at a university in Europe. Her death in a flood in 1261 prompted the suspension of classes in her honor.

Laura Bassi: The enlightenment scientist

Nearly five hundred years later, Bologna produced another academic first. Laura Bassi was born in 1711 and tutored privately, her intellect quickly drawing the attention of Cardinal Prospero Lambertini, who would later become Pope Benedict XIV.

At the age of twenty-one, she publicly defended forty-nine theses, earning a doctorate in philosophy and science, the first woman in Europe to do so in science. That same year, she was appointed as a professor of natural philosophy, making her the first salaried female university professor in the world.

Bassi went on to become a leading figure in the promotion of Newtonian mechanics in Italy, teaching and conducting experiments both at the university and in a laboratory she shared with her husband.

In 1776, she was appointed to the chair of experimental physics, a post she held until her death two years later. She corresponded with some of the most prominent scientists of her era, including Voltaire, and left behind a body of work that secured her place in the history of European science.

Why their achievements matter

In eras when women were almost entirely excluded from higher education, both Gozzadini and Bassi gained entry not as anomalies, but as respected scholars in fields central to Bologna’s reputation.

Their roles challenged prevailing norms and demonstrated that intellectual authority need not be limited by gender. Though centuries apart, they share a place in the same historical arc, one that begins in the medieval legal tradition and extends into the experimental sciences of the Enlightenment.

The willingness, however rare, of the University of Bologna to recognize female scholars set it apart from most of its contemporaries.

Over time, it became home to other remarkable figures in academia. Mathematician and philosopher Maria Gaetana Agnesi was among the first women to write a mathematics handbook and to be appointed a university professor. Linguist Clotilde Tambroni lectured on Greek and literature in the 18th century. The naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi established one of Europe’s first botanical gardens and advanced the study of natural history. In the 20th century, novelist, philosopher, and semiotician Umberto Eco shaped the modern study of communication from within its walls.

These names form a continuum of scholarship that reflects Bologna’s enduring capacity to produce and attract exceptional minds. Bettisia Gozzadini and Laura Bassi remain its earliest examples of women at the lectern, a precedent that, centuries later, still carries weight in the conversation about who belongs in the world’s oldest seats of learning.

.jpg)