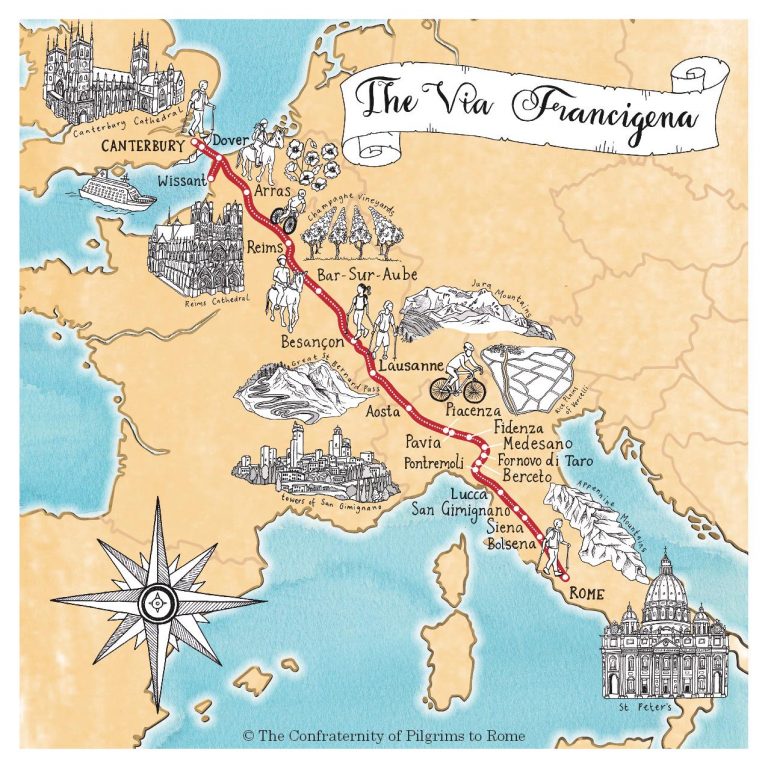

Centuries before low-cost flights and GPS, a steady procession of pilgrims forged a path from Canterbury Cathedral to St. Peter's Basilica. Known today as the Via Francigena, this ancient artery threaded through four centuries, yet what endures most is its heartbeat—a living journey resurrected in purpose and shared humanity.

The story begins in the late tenth century with Archbishop Sigeric of Canterbury. His meticulously kept record of 79 relay stations, so called mansiones, between England and Rome became the blueprint.

Yet, archeological traces and medieval writings suggest this road was already millennia old: Romans, Lombards, medieval clerics and merchants, all made use of these routes which linked northern Europe to papal authority and Mediterranean trade.

A pilgrimage rooted in reflection

Although it fell into obscurity amid shifting trade routes and the later dominance of the Camino de Santiago, interest in the Via Francigena was rekindled in the 1980s. Officially recognized in 1994 as a Cultural Route of the Council of Europe, the trail has, since the mid-2000s, been restored and waymarked across Italy, France, Switzerland and England.

Today, where stone relics had faded, vibrant red, yellow, and white pilgrimage markers guide wandering souls once more.

But those signs are only part of the story. Walkers who set out in 2024 found infrastructure that feels less like tourism and more like gentle hospitality: agriturismi, parish hostels, luggage-transfer services. Around 87 percent traveled on foot, 13 percent by bicycle, and a few chose horseback—modern echoes of medieval travel. In Rome alone, nearly 6,000 received the official Testimonium in 2024, nearly double the previous year, with even more expected during the 2025 Jubilee.

These numbers, though modest compared to the Camino, represent a pilgrimage rooted in reflection rather than recreation. Data gathered by the European Association reveals pilgrims are equally motivated by cultural curiosity and spiritual searching; those walking with a companion slightly outnumber those alone. There is a particular balance between youth and long-lived reverence: ages 25–34 and 55–64 lead the way, with a nearly equal gender split.

Serenity amid chaos

Beyond stats, what draws modern travelers is the route’s restorative rhythm. As one pilgrim writing in early 2025 put it, she sought serenity amid "chaotic political upheaval" in her homeland, finding solace each morning in the hush of monks’ chants or the quiet swirl of Tuscany’s vineyards. Another described the experience as a space “permitted… to need and accept help,” where dependence becomes grace.

The Via Francigena stretches over 2,000 km through rugged passes and quiet farmland. But the route’s structure with segments of a week or more, lets walkers assemble their journey in stages. The concluding 100 km into Rome alone qualifies one for the Testimonium; the final southern extension to Puglia, ways beyond the Alps, is less traveled, quieter, and rooted in rural authenticity.

What kind of traveler does the Via Francigena call? It asks for patience more than ambition and openness more than solitude. At each stop, be it an ivy-hung hospice, a medieval bridge, or a Tuscan trattoria, pilgrims encounter Europe's layered story. It’s a path that revives the refrain of shared humanity: a butcher from Siena, a Swiss hermit, a French volunteer, all offering directions, water, fellowship. In those everyday exchanges echoes grow: of Belloc’s pilgrims under the moon and fireflies, rediscovering “whatever benediction surrounds our childhood.”

As Europe prepares for the 2025 Jubilee, the route’s revival forecasts more than renewed footfall. It restores a slower, more reflective pace to spiritual and cultural exploration. In walking the Via Francigena, one does not simply arrive in Rome; one carries centuries of devotion in the soles of one’s boots and the depths of one’s heart.