Few trains carry the weight of myth like the Orient Express. Known through novels, cinema, and decades of cultural reference, it has come to symbolize rail travel at its most refined.

The modern Venice Simplon-Orient-Express, launched in 1982, revived that image with painstakingly restored 1920s and 1930s carriages, transforming them into a moving hotel that still links Europe’s major capitals.

Reviving the legend

The Venice Simplon-Orient Express (VSOE) operates restored Compagnie Internationale des Wagons Lits carriages dating from the 1920s and 1930s. In 1982, American businessman James Sherwood acquired and refurbished these historic vehicles, reviving service under the VSOE name. The inaugural journey from London to Venice began on May 25, marking the train’s modern-day return to service.

The continental consist currently includes eighteen carriages: twelve sleeping cars, three dining cars, one bar car, and two support wagons used for staff accommodation and supplies. Safety and comfort have been upgraded; air conditioning was installed in 2017, and the original bogies were replaced to allow speeds up to 160 km/h.

Passenger accommodations are segmented into several tiers:

Historic Cabins preserve the original compartment layout without private bathrooms.

Suite class sleepers, introduced in 2023, feature convertible bed configurations and design themes tied to European landmarks such as forests, lakes, and mountains.

Grand Suites debuted between 2018 and 2020 and include a drawing saloon, sofa convertible into a bed, and private bathroom.

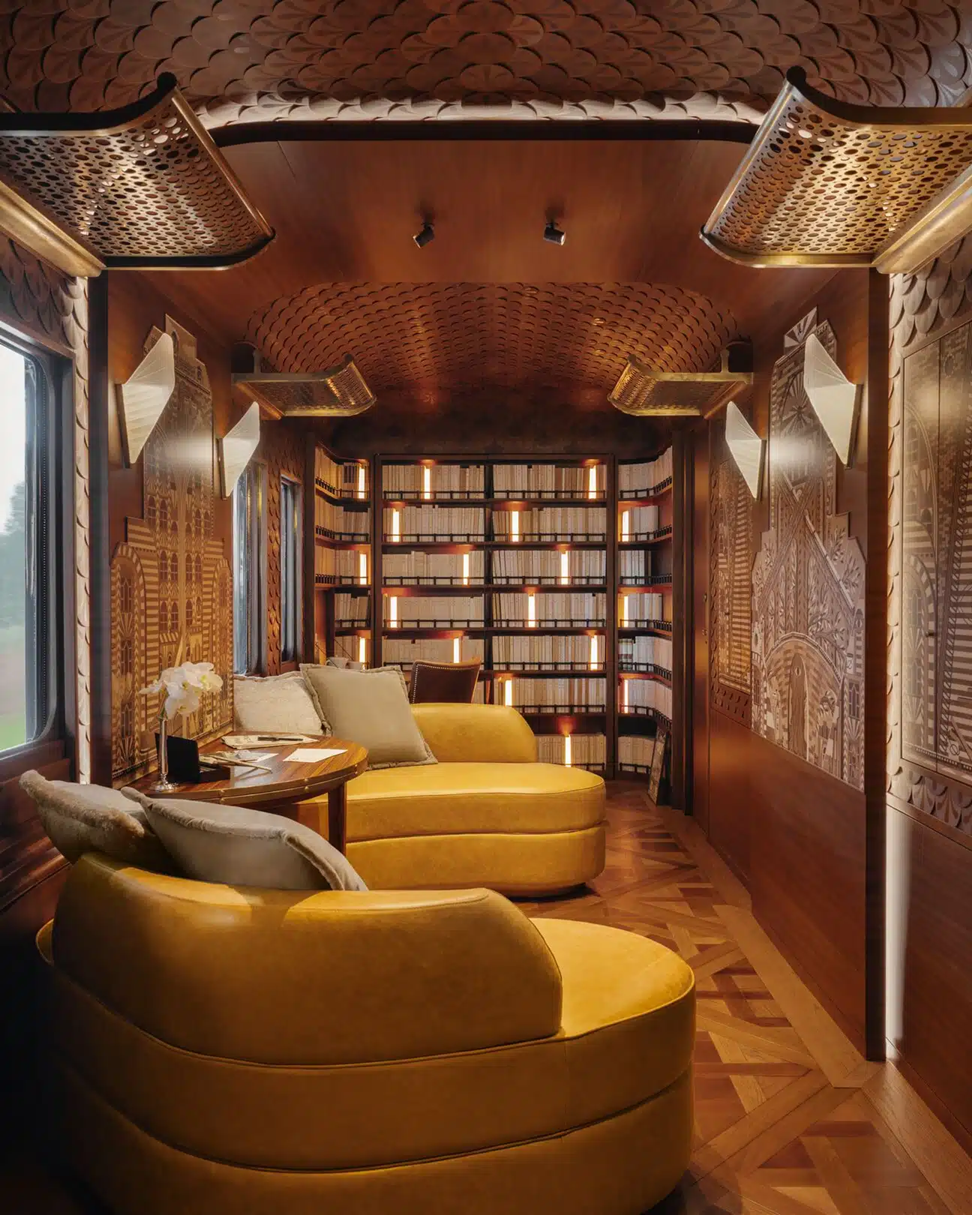

A new private carriage, L’Observatoire, debuted in 2025. Designed by the French artist JR and built using traditional marquetry techniques in collaboration with Atelier Philippe Allemand, this carriage integrates a bedroom, lounge, library, tea chamber, and a bathroom complete with a bathtub.

JR's creative concept draws inspiration from astronomical observatories and Renaissance cabinets of curiosity; the interior incorporates personal art pieces and detailed marquetry intended to provoke discovery.

Lalique-lit dinners

Dining is a hallmark of the VSOE experience. Passengers are served meals prepared on board in three distinct dining cars—L’Oriental, Étoile du Nord, and Côte d’Azur—each showcasing unique period décor.

The Côte d’Azur car, for example, features ornate glass panels by René Lalique. The bar car, originally a restaurant carriage, is equipped for evening service with cocktails, live music, and staff dressed in formal uniforms. Passengers are expected to observe formal dress codes, particularly during dinner.

The train follows several well-established routes. The classic journey runs between London, Paris, Milan, and Venice via the Simplon Tunnel, with alternative pathways through the Brenner Pass serving Zürich, Innsbruck, and Verona. Occasional departures extend to Prague, Vienna, and Budapest.

The once-a-year extension to Istanbul, including overnight stays and sightseeing, continues to operate when regional conditions permit. Special seasonal routes have included destinations such as Cannes, Rome, Florence, Brussels, and Amsterdam.

Culture in motion

Cultural touchpoints keep the train in public imagination without needing constant reinvention. Agatha Christie’s “Murder on the Orient Express” supplies an instantly recognizable narrative frame; every departure inherits a hint of locked-room intrigue, correct or not. Wes Anderson’s train worlds show how design, pacing, costume, and lighting can turn transport into a set piece.

The Venice Simplon-Orient-Express leans into that idea with period interiors, formal service, and a choreographed evening routine that feels deliberately staged. Add commissioned projects like JR’s L’Observatoire and the result is not nostalgia for its own sake but a working case study in how culture, craft, and operations can align to create theatre at speed across Europe.